SHOULD UTILITIES INVEST IN LARGER SCALE, LARGER UAS OPERATIONS? ...MAYBE.

- 2 days ago

- 12 min read

February 2026

Co authored by: Nate Ernst, President, The Tactien Group; Charlton Evans, CEO, End State Solutions; Ed Celiano, VP, The Tactien Group

Capability, Regulatory Pathways, and Real World Adoption

Across the utility industry, unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) have moved well beyond the “proof-of-concept” phase. What began as small drone pilot programs supporting visual inspections and storm response has evolved into enterprise-scale operations supporting transmission inspection, vegetation management, emergency response, and other evolving use cases. Linear infrastructure writ large is an ideal use case for autonomous airborne operations.

As these programs mature, a new question is becoming increasingly common - “Should utilities invest in larger UAS operations?”

The answer is not a simple yes or no. Instead, utilities should invest in larger UAS when the mission demands such and only when the organization understands the true costs associated vs. current capabilities. As more utilities consider stepping into larger platforms beyond Group 1, exceeding 55 pounds, operating outside standard Part 107 frameworks, or supporting advanced payloads, leaders must evaluate more than aircraft performance alone. Regulatory viability, operational safety, and unit economics all become critical decision factors.

Nate Ernst, President of Tactien, frames the issue clearly: “Larger UAS adoption is not a technology decision. It is a business decision. If the platform does not offset costs, whether direct or indirect, reduce outage time, improve reliability, or reduce risk exposure, it is not a viable pathway. In that case, it becomes nothing more than an expensive science fair project.”

As Charlton Evans, CEO of End State Solutions, notes, “The data requirement drives sensor requirements which drives aircraft type and size.”

This article offers a pragmatic view of the business case, the pros and cons, the primary regulatory approval pathways, and practical tips for utilities considering larger UAS adoption.

Business Case Reality

Large UAS can provide meaningful operational advantages, but only when aligned to a clear mission of need. Too often, organizations approach larger UAS as the “next step” in program maturity. Larger UAS is not a natural progression. It is a different class of capability and complexity with different levels of risk, cost, and regulatory burden. Utilities must consider the following when considering advanced UAS operations:

Total system (not just aircraft) capability

Total system cost (direct and indirect)

Cost justification

Total value proposition (beyond direct mission tasks)

The successful business case for larger UAS does not come from beating manned aviation/alternative methods on direct cost. Conservations started with a simple “UAS flight-hour versus helicopter flight-hour” comparison will collapse.

Larger unmanned systems (over 55 lbs.) bring higher maintenance demands, more specialized staffing, more rigorous compliance overhead, and a deeper operational support footprint. Direct cost parity flips and the UAS operation becomes more expensive on an apples-to-apples, line-item basis.

Ernst offers a clear warning to utilities building their business case around direct cost comparisons. “If your business case solely relies on being more cost effective than a helicopter or fixed wing, larger UAS is not for you. Not right now anyway. Large UAS wins when you account for the indirect burdens that are carried…hazardous labor hours, insurance premiums, operating overhead, etc. If the system is not multi- (and concurrent) mission capable, with data that is utilized by multiple departments, there is zero business case for advanced UAS.”

The goal is not “advancing UAS capability within your program.” The goal is a reliable, scalable unmanned capability that reduces fully burdened, risk-adjusted cost and creates repeatable enterprise value.

“When utilities treat large UAS as an enterprise aviation capability, measured on total value rather than direct parity, the decision becomes clearer and the likelihood of success improves.”

Large UAS can provide meaningful operational advantages, but only when aligned to a clear mission of need. Too often, organizations approach larger UAS as the “next step” in program maturity. Larger UAS is not a natural progression. It is a different class of capability and complexity with different levels of risk, cost, and regulatory burden.

Utilities must consider the following when considering advanced UAS operations:

Total system (not just aircraft) capability

Total system cost (direct and indirect)

Cost justification

Total value proposition (beyond direct mission tasks)

The successful business case for larger UAS does not come from beating manned aviation or alternative methods on direct cost. Conversations started with a simple “UAS flight hour versus helicopter flight hour” comparison will collapse.

The Pros

Increased Payload and Mission Capability

Larger UAS platforms allow utilities to carry heavier payloads, operate longer per flight, and fly further down range than sUAS. These platforms also enable mission designs that are impractical with small UAS, particularly when endurance and payload integration determine operational success. It is a different level of unit economics.

Safety Improvement Through Risk Reduction

Utilities operate in environments where the most serious incidents often stem from falls, remote terrain exposure, and aviation risk. Reducing human exposure from hazardous environments is not just a cost saving measure. It is a safety and resilience strategy.

Cost Efficiency at Scale

Large UAS can become financially compelling when deployed in high volume, recurring workstreams, particularly those that rely on crewed aviation or labor intensive field activities. At scale, the ability to mobilize quickly, fly longer, and collect higher quality data can materially shift a utility’s cost curve.

The Cons

Regulatory Complexity

Unlike small UAS operations that can often be managed under Part 107 waivers or limited Certificate of Authorization (COA) frameworks, larger UAS programs require deeper engagement with FAA approval processes. This includes more extensive documentation, more rigorous safety cases, and longer timelines. When the new Part 108 rules are released as final there will be a clearer regulatory path, but do not be surprised if that path is still an arduous one.

Higher Operational Burden

Many utilities underestimate the operational infrastructure required to maintain advanced UAS programs. The flight operation is only the forward facing aspect. Running a sustainable operation requires strategic thinking, training programs, maintenance frameworks, safety oversight, mission planning processes, and governance.

Higher Upfront Costs and Program Risk

Acquiring a platform is only a fraction of the cost. Training, regulatory approvals, spares, maintenance, documentation, and organizational integration are what determine whether the investment succeeds. Without a clear mission case and a mature operational model, a large UAS program can become a stranded asset, an impressive aircraft without a viable deployment pathway.

If the mission case supports a larger UAS investment, the next question becomes: how can utilities legally and safely operate these systems, and are any of these pathways viable right now? Today, two primary pathways make the most sense:

Section 44807 Exemptions AND 14 CFR 91.113(b) “Detect and Avoid” waivers

Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations (PAO) and 14 CFR 91`.113(b) “Detect and Avoid” waivers

Each pathway has benefits and limitations. Regardless, these pathways are both journeys, far more than a simple application. As Evans explains, “The FAA’s charter is to ensure aviation safety. Those going after advanced approvals are held to an equivalent level of safety discipline, documentation, and operational maturity to a similar manned operation, not just enthusiasm.”

Pathway 1: Section 44807 and 14 CFR 91.113(b), Detect and Avoid Relief

What it is

Section 44807 is a regulatory mechanism from the FAA’s Reauthorization Act allowing the FAA to grant exemptions for certain aircraft operations outside the standard certification framework. In practice, 44807 is often used to enable specialized operations with defined limitations and risk mitigations.

Best fit

The 44807 pathway is best suited for pilot programs, demonstrations, or early stage operational testing where the utility wants to establish initial capability and operational credibility. This pathway is best suited for utilities that have well defined operational areas, airspace control mechanisms, and safety mitigations that can be clearly explained and defended.

“A 44807 exemption can be a great door opener, but utilities need to understand what it is and what it is not. It is not a shortcut to full scale operations. It is a structured way to prove capability under defined conditions. Depending on your CONOP, the 91.113(b) can be challenging. The rule is about right of way and detect and avoid responsibilities, but utilities must demonstrate a credible detect and avoid concept and prove it. If you cannot explain how you are preventing midair conflicts, you do not have an operational approval pathway.”

Pathway 2: Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations (PAO)

What it is

Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations (PAO) is a pathway that often gets overlooked. However, if implemented correctly, it can be one of the most viable, flexible, and self governed frameworks for qualified utilities aligned with public aircraft eligibility requirements. This pathway is frequently associated with government agencies and public safety operations but can also apply to critical infrastructure utilities depending on the organizational structure and the CONOPS.

Part 91 is not simply a regulatory label. It is an operational commitment. Utilities must demonstrate aviation grade governance, disciplined safety processes, and a strong compliance culture. The flexibility of Part 91 operations comes with heightened responsibility.

Best fit

The Part 91 pathway is best suited for utilities with mature UAS programs and recurring mission demand, especially those seeking an enterprise model rather than a limited pilot program.

Ed Celiano, Vice President of Tactien, emphasizes that success under this framework depends less on the aircraft itself and more on the maturity of the organization operating it. As Celiano notes, “Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations can be one of the most effective pathways for utilities but only if the organization takes governance seriously. PAO gives flexibility, but it also demands discipline. Utilities succeed under PAO when they build a real aviation program, standardization, training, maintenance, safety oversight, and clear operational authority. If it’s treated like a side project, it won’t scale.”

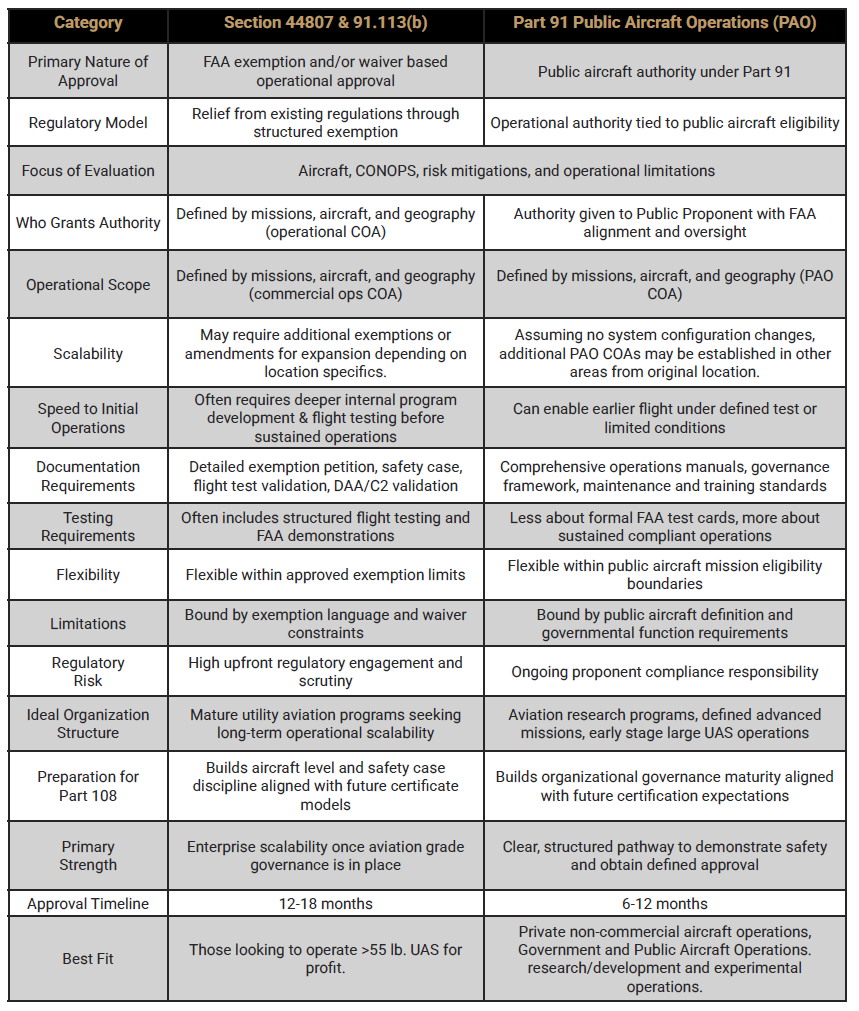

Comparison Summary: 44807 vs Part 91

FIGURE 5 : (above) Single and multi-state COAs (examples)

The following comparison outlines the fundamental differences between the Section 44807 and 91.113(b) pathway and the Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations pathway. The intent is to provide a general understanding of how each model functions, where the emphasis lies, and how they differ in structure and scalability. This comparison is intended for high level reference only. The appropriate pathway for any given utility will depend on mission objectives, organizational maturity, aircraft type, and long term operational strategy. A detailed analysis tailored to the intended operator may lead to different conclusions based on specific circumstances.

What about Part 108?

Part 108 is often referenced as the future regulatory framework for advanced UAS operations, particularly those involving larger aircraft, higher risk profiles, or expanded operational authority. For many utilities, the prospect of Part 108 raises a reasonable question: should organizations wait for this rulemaking before committing to advanced operations?

The short answer is no. Waiting for Part 108 is unlikely to accelerate operational readiness and may delay meaningful development of capability. It is also important to remember that Part 108 is limited to 400 feet AGL. 44807 and Part 91 operations have ceilings that are Concept of Operation (CONOP) defined, which could be greater than 400 feet.

It is important to recognize that the current Section 44807 exemption process has effectively served as the foundation for the Part 108 certificate model. The safety cases, operational concepts, documentation standards, and risk mitigations required under 44807 mirror many of the principles expected to underpin Part 108 certification. In practice, utilities operating under 44807 and related frameworks are already doing the work that Part 108 will ultimately formalize.

Just as importantly, these pathways actively prepare organizations for Part 108. Utilities that have developed disciplined operations, trained crews, maintenance programs, safety oversight, and regulatory engagement through 44807 and 91.113(b) are far better positioned to transition into a certificated environment when Part 108 is introduced. The operational maturity developed today will not be lost or replaced. It will be carried forward.

There is also significant uncertainty around the timing and structure of Part 108. While the rulemaking process continues, there is no clear timeline for rollout, and it is reasonable to expect that initial implementation will prioritize more mature and lower risk permitted operations. Advanced, high consequence missions are likely to be phased in over time rather than approved immediately upon release. Even if Part 108 were finalized tomorrow, widespread approval of complex utility operations would almost certainly come later.

For utilities, the practical takeaway is this: existing pathways allow organizations to become operational sooner while also preparing for the future regulatory landscape. Section 44807, 91.113(b), and Part 91 PAO enable real world operations today, build regulatory credibility, and create a foundation that aligns with the direction of Part 108. Rather than competing paths, they are stepping stones that allow utilities to move forward deliberately, safely, and with confidence.

Considerations

Utilities exploring large UAS adoption should approach the decision like a major aviation initiative, not a technology purchase.

1. Start With the Missions, Not the Aircraft

Large UAS platforms are tools. The mission must justify the complexity. Utilities should clearly define what operational gap exists and whether it cannot be better solved by small UAS, crewed aviation, or ground based alternatives.

2. Recognize True Timeline and Organizational Readiness

FAA approvals, training, documentation, and operational development often take longer than expected. Programs fail not because the aircraft cannot fly, but because the organization cannot sustain the operational requirements required during the regulatory approval process. This is a journey that demands patience, resourcing, and long term organizational commitment.

3. Build an Aviation Operation, Not a Drone Team

Large UAS requires aviation level standardization. That includes maintenance programs, safety management, training requirements, and defined authority structures.

4. Consider Strategic Partnerships, Especially Educational Institutions

Partnering with universities and educational institutions provides access to test environments, COA development, research support, training pipelines, and collaborative development.

5. Engage with the right Operational SMEs Early

One of the most common pitfalls utilities faces is relying too heavily on aircraft manufacturers, platform vendors, or industry rumors to define operational strategy. Vendors can provide valuable insight, but they are biased, and they are not responsible for the utility’s operational safety case. Organizations who have led such efforts in the past and are interested in knowledge transfer for the success of your program become assets for success.

6. Understand the aircraft, OEM, and subsystem food chain entirely

Utilities should fully understand the aircraft, the OEM, and the entire subsystem ecosystem before making a major investment. The UAS industry continues to evolve quickly and, in most cases, remains volatile. Performance claims do not always translate into operational reality, and long term program success often depends as much on the OEM’s stability and supply chain relationships as it does on the aircraft itself. This is a significant investment, and utilities cannot afford to commit to a platform without validating performance, supportability, and the long term viability of the manufacturer.

7. Have program contingency plans

Even well planned programs encounter unexpected obstacles. Utilities should assume that setbacks are possible and plan accordingly.

What happens if the aircraft does not perform as advertised?

What happens if the OEM experiences delays, staffing issues, or supply chain disruption?

How will the program continue if parts availability becomes constrained or vendor support declines?

Strong programs build resilience early by identifying these potential pitfalls, defining decision thresholds, and establishing contingency options that protect the utility’s operational capability and investment.

Closing Thoughts

Larger UAS operations represent one of the most promising emerging capabilities in the utility sector. They offer a meaningful opportunity to improve safety, reduce exposure in hazardous environments, and unlock new operational efficiencies. At the same time, these programs require utilities to navigate unfamiliar regulatory terrain, develop aviation grade operational discipline, and make decisions with long term strategic implications.

Many utilities are already pursuing this path, and the challenges they are encountering should not be interpreted as failure. They reflect the complexity and significance of building a true aviation capability inside an infrastructure organization. Success rarely comes from speed alone. It comes from aligning the capability to real mission needs, selecting a regulatory pathway that matches organizational maturity, and building operational discipline deliberately over time.

That discipline extends beyond aircraft selection. Celiano emphasizes that utilities often run into difficulty when they rely too heavily on manufacturers for operational guidance. As he notes, “The biggest mistake utilities make is relying solely on manufacturers for operational guidance. The aircraft vendor is not your operator, your regulator, or your safety manager. You need unbiased SMEs who have lived the operational reality.”

Regulatory success also depends on mindset. Evans notes that utilities who approach approvals as structured engineering efforts tend to progress more efficiently and with fewer surprises. In his words, “When utilities treat the approval process like an engineering project, with requirements, mitigations, and testable assumptions, the regulatory pathway becomes manageable. When they treat it like paperwork, it becomes painful.”

Ultimately, the investment decision must return to enterprise value. Ernst reinforces that advanced UAS programs should not be justified by novelty or aircraft ownership. As he explains, “The goal is to run a safe, repeatable operation that produces measurable value. When utilities focus on outcomes instead of equipment, the decision becomes much clearer.”

When approached deliberately and thoughtfully, larger unmanned systems can be integrated safely, legally, and sustainably. For utilities willing to invest in governance, operational maturity, and sound regulatory strategy, advanced UAS can strengthen both operational performance and organizational resilience for years to come.

About the Authors

The Tactien Group is a leader in advanced UAS operations supporting critical infrastructure, with deep experience developing and executing programs under Section 44807 exemptions, 14 CFR 91.113(b) operational frameworks, and Part 91 Public Aircraft Operations. Tactien works alongside utilities to build scalable, aviation grade UAS programs that are safe, repeatable, and defensible. In addition to operational development, Tactien supports utilities with business case development, program strategy, and ROI validation. Through a pragmatic approach grounded in realworld flight operations, Tactien helps utilities turn advanced UAS capability into sustainable enterprise outcomes.

End State Solutions (ESS) is a trusted advisor in advanced UAS regulatory strategy and FAA engagement, with a proven track record supporting clients through complex Section 44807 exemption processes and 14 CFR 91.113(b) operational approvals. ESS specializes in building credible safety cases, developing regulatory documentation, and helping organizations navigate FAA requirements with clarity and discipline. With extensive experience in advanced UAS approvals and operational integration, ESS helps utilities and operators accelerate regulatory success while ensuring programs are structured for long-term sustainability. Through deep regulatory expertise and practical execution, End State Solutions enables organizations to confidently pursue

advanced operations that stand up to scrutiny and scale.